Where Do We Come From? Who Are We?

Where Are We Going?

Monarchy and the West: A Meditation

I originally wrote this piece, The Sleeping King, ten years ago in a post-9/11 ambience, where I was looking to define a set of clear Western values in distinction to the alternative worldview posited by radicalised Wahabi Islam. At the time I was very much under the intellectual influence of the Traditionalist school, with writers like René Guénon and Frithjof Schuon (both Muslim converts interestingly) playing a major part in my philosophical and spiritual formation.

I'm not quite so engaged, these days, with Traditionalism, though it remains a key reference point in my thought and work. So, if I was writing the piece again today, I would probably show a touch more generosity to the 'bottom-up' democratic approach, and maybe downplay a little the 'top-down' hierarchical angle. I've slightly shortened things, just to lose a bit of repetition, but apart from that there isn't really much I'd change. I might have been slightly harsh on the French Revolution in places, and I'm not sure Napoleon was quite the 'Arthurian figure' I cracked him up to be, but still. The essay also does not take into account the marriage of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge in 2011 and the Queen's Diamond Jubilee a year later, two events which provoked much chit-chat regarding the monarchy here in the UK.

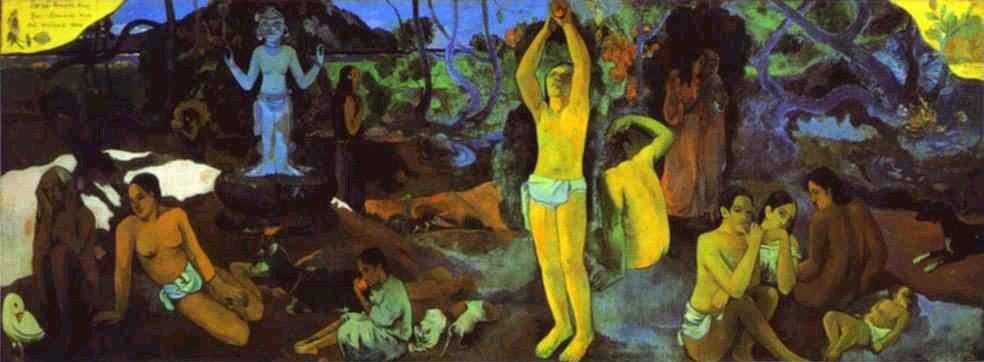

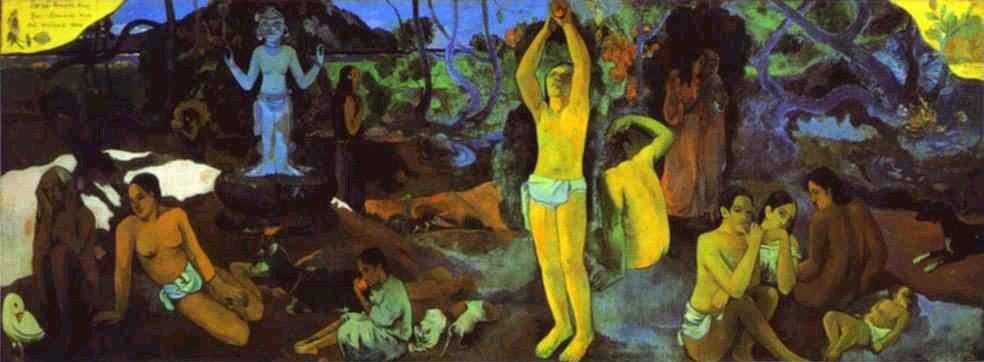

One could argue that the moment of clarity I was grasping for in 2003 became dissipated and subsequently lost in military misadventures, not so much in Afghanistan, perhaps, but almost certainly, in my view, in Iraq. But in another sense, nothing has changed. We're still where we were - the same challenges facing us today as yesterday. The questions that exercised my mind in the Anthony Burgess review below are played out here again, this time on the civiliasational level as well as the individual. What is the West? What is it for? What does it do? In the words of Gauguin's famous painting: D'où venons nous? Que sommes nous? Ou allons nous? The concept of monarchy, so deep-rooted and archetypal in the Western imagination, suggests, for me at least, a couple of bricks and a tiny bit of mortar with which we might be able to begin crafting (or recrafting) an intellectual and spiritual structure, not unlike the great cathedrals of old perhaps, of real interest and permanent value.

The Sleeping King

Beauty is not only a terrible thing, but also a mysterious thing. There God and the devil are fighting for mastery and the battlefield is the heart of man.

Dostoyevsky, The Brothers Karamazov.

'The Kingdom of Heaven lies within'. Endless repetition might have dulled our senses somewhat to the significance of this phrase, so it is worth re-iterating that, in the last analysis, all things of value lie within the human heart and imagination. This is not to imply that there is only the human heart and imagination. Far from it. The inner and the outer interlink and dovetai togetherl, a prime example being our latent sense of royalty, this intangible but seemimgly inbuilt human awareness of a royal principle at work through the vicissitudes of the historical record.

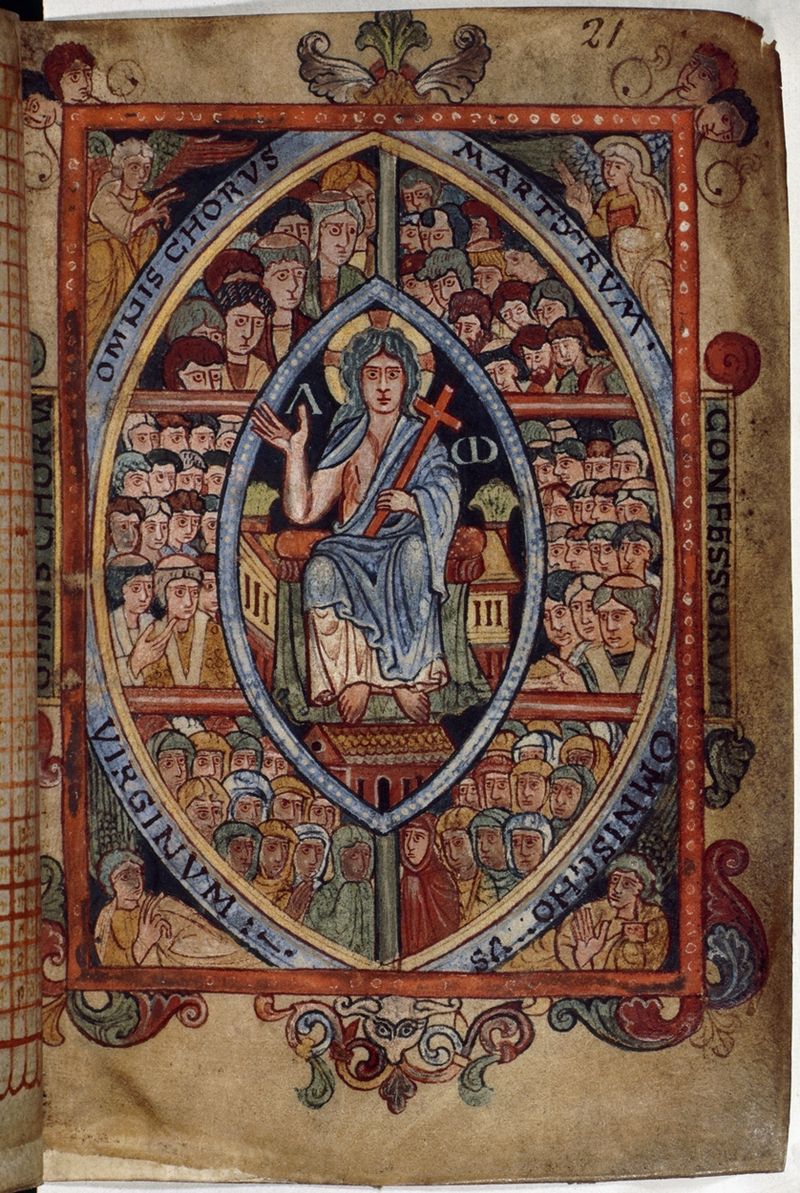

Monarchy, seen in this light, is a natural and organic form of government, understood intuitively by individuals from widely varying backgrounds and levels of intelligence. Legitimacy is conferred from above (the Divine) rather than below (the people), but monarchy remains part of the natural order and stands at a substantial remove from some random and artificial 'system' of government imposed on a pliant, submissive population. The monarch is a symbol of his or her people's liberty - a guarantor of freedom of conscience and speech - existing not so much to rule as to serve. This Christological function finds expression in, among other places, the legendary cycle of King Arthur and his knights, where we find a body of lore and a central mythological motif common throughout the West and beyond - that of the sleeping king, destined to wake at his country's hour of need.

The hold of monarchy on the human imagination is markedly weaker today than at any time in the past. The days of Charlemagne and Athelstan are long gone. Since the decline of the Middle Ages the focus and dynamism of the West has tended to revolve around the external world, to the detriment of the inner milieu that animated Medieval mystics such as Julian of Norwich, and inspired the construction of the great cathedrals of Chartres, Reims, York, Durham, etc. Western society has been de-sacralised and rationalised to such a degree since that it has become increasingly difficult for what we might call 'supra-rational' concepts like monarchy and contemplative, religious mysticism to gain any degree of purchase in the contemporary imagination.

This link between Divinity and royalty is a crucial one. In a well-ordered polity the sovereign acts as God's regent; so when, for example, the Medieval French kings abrogated power from the Pope, they unwittingly undermined their own legitimacy and raison d'être. Their lust for hegemony only succeeded in tipping the balance of the natural order askew and sowing the seeds of their own destruction.

Once this natural harmony is thrown out of kilter it becomes very difficult to restore the balance. The French Revolution and the bloodletting which followed are fine illustrations of the chaos which can often result from a shaken hierarchy. In the 1790s, however, matters had not yet descended to such a pass that the situation was wholly irretrievable, and Napoleon's more or less principled autocracy restored a little of the equilibrium and saved France from unmasked brutaliy. But by 1917 the world had been de-spiritualised to such an extent that the fall from revolution to tyranny was able to take place largely unimpeded. An Arthurian figure like Bonaparte would have been unable to make an impression on post-1917 Russia simply because he belonged to a different era where the royal principle still commanded a central (if somewhat diminished) position in hearts and minds.

C.S. Lewis famously remarked that 'one can tell the extent to which a man's tap root to Eden remains intact by his attitude to monarchy.' Inner and outer harmony begin to disintegrate when this tap root, this intangible and utterly mysterious quality is weakened and subsequently severed. If man - the microcosm - falls into step with natural hierarchical patterns, then the outer world - the macrocosm - flows likewise in a harmonious fashion. The human heart is the point where microcosm and macrocosm meet, and it is here that the future of monarchy - our very own future as a thinking, acting species with choice and fee-will, in other words - will be decided. The heart is the throne of the 'sleeping king'. We will flounder and struggle to restore kudos and depth of meaning to royalty in the outer world unless we come to acknowledge this royal aspect within.

The task will be difficult. We live in an obtuse, chatter-filled, technologically-driven age, where talk of 'hidden kings' and suchlike will inevitably appear obscure and inaccessible. Nonetheless, the responsibility and challenge is ours to start setting some kind of creative, imaginative agenda - through literature, art, film, music, dance, drama, politics and philosophy. There are forces arraigned against us, powers of iron and stone, seeking to rob us of vision, reducing us to impotent cogs in a vast collective machine or, failing that, to mindless, zombified consumers, the hungry ghosts of Buddhist icongraphy.

It isn't good enough. Not for the West. Not for human beings. We are more, much more, than economic units shuffling around like atoms in some demented 'free-market' disco. Our lives are more, much more, than a shapeless, rough and tumble scramble for comfort and security. Life is, or ought to be, an adventure, an exercise in nobility, and the traditional job of monarchy is to serve as role-model and exemplar in that respect.

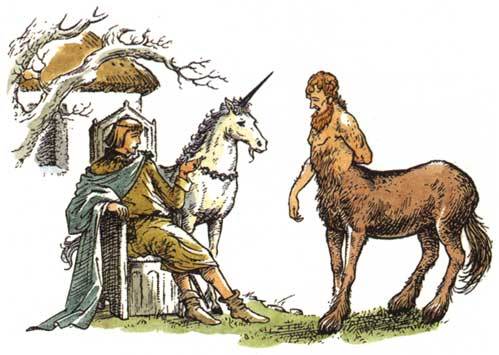

As for us - as for the future - well, the revolution starts from within, with a heightening in our level of consciousnes and a deepening of our perception. Our task, our mythological function and responsibilty, is a twenty-first century quest for the Golden Fleece - to unveil the monarch within, and awaken the sleeping king.

*******

P.S. This motif of the sleeping king has exercised my mind for many years. Must be something to do with reading

The Weirdstone of Brisinganen when I was very young and bobbing down to Alderley Edge a couple of times with my dad :-) Anyway, the same theme is at the centre of a new short prose piece,

Phoenix Fire, and the twelve haiku that go along with it. Written from the perspective of a former French Resistance fighter, the work explores the intellectual, spiritual and mythological links between Britain and France. Created in partnership with the fine artist, Rob Floyd (

www.robfloyd.co.uk),

Phoenix Fire will be featured at this year's Didsbury Arts Festival (22/06 to 30/06). The venue is Christ Church in West Didsbury and I shall be previewing the prose piece on this site nearer the time.

All the best, jf.